What is the Budget Gap?

January 6 – By law, the City of Chicago is required to have a balanced budget, whereby projected expenditures match projected revenues, across all funds. Funds include the City’s “discretionary” general fund (“Corporate Fund”), where most of the governmental services you rely on. As of this writing (December 22, 10:00am), the City Council has passed substitute 2026 Budget Recommendations; Management Ordinance; and Revenue Ordinance documents that amend the administration’s proposed budget. These amendments raise new discussions about what a balanced budget is, because they use speculative and untested revenue sources, resulting in a likely budget gap. While the City’s Budget Director, Comptroller, and Chief Financial Officer used a Wednesday, December 17 budget hearing to discuss the assumptions of this budget at length and demonstrate that it is at least $160,000,000 out of balance, one does not need the administration’s numbers alone to test the assumptions of this budget.

This budget blog:

Reviews the City Council-led (so-called “alternative”) budget at length

Reviews the Chicago Public Library property tax levy

Reviews legally required costs that are contributing to revenue pressures

Reviews eleven aspects of budget-related revenue and expenses that are placing pressure on the budget.

Discusses more than $1.7 billion areas of policy in the City, in order to fully assess budgetary pressures.

Discusses why cuts are a difficult option to resolve the Corporate Fund gap

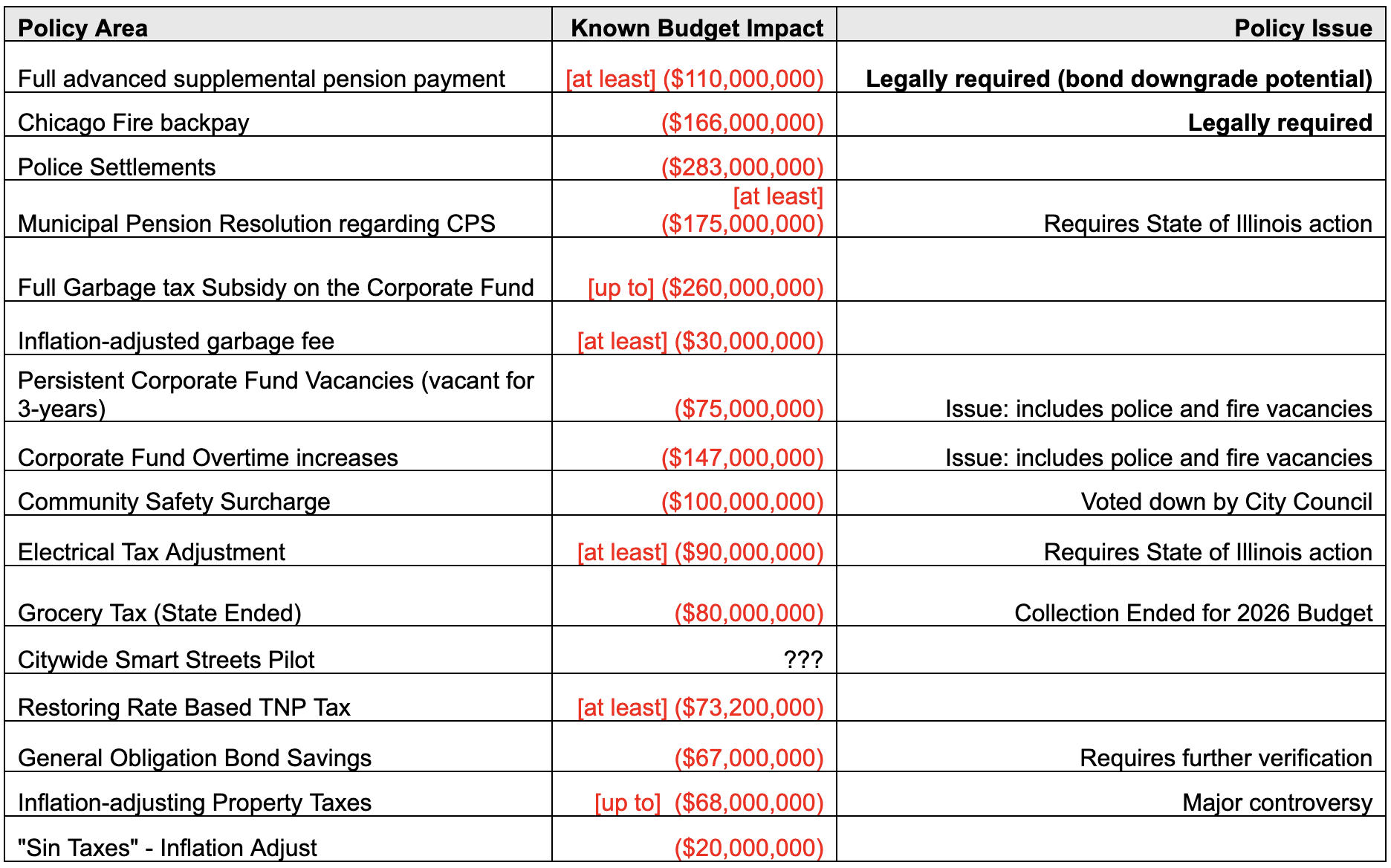

Summary of Budgetary and Policy Items Discussed in this Blog - $1.7 Billion Areas of Budget Impact

How did City Council balance the budget?

Here are the major revenue assumptions that differed from the administration:

$89,600,000 – Fines, Fees, & Forfeitures: The City’s budget is now balanced on the assumption that the City can sell $1,000,000,000 in unsecured debt for pennies on the dollar, to raise roughly $89 million instead of raising a Corporate Head Tax (Community Safety Surcharge). This was the major debate of the budget cycle.

Unsecured debt means that the City would not be selling an asset to secure the debt. This means that the City would need to sell solely the right to collect the debt, and nothing more. The City regularly sells secured debt, which provides the buyer with an asset. For example, when the City sells a bond, there is a security with certain pledges (such as property tax revenues) and legal protections that make the investment more sound. With unsecured debt, the City would likely only be selling the right to collect the debt, and nothing more. For example, in this case, the City is not even selling liens against properties – even a lien would provide more of an asset to a debt buyer, rather than simply purchasing the right to collect the debt.

More importantly, beyond the principal of selling unsecured debt, there is no Municipal Code amendment to manage the debt in the Substitute Management Ordinance (ordinance that amends the Municipal Code to implement the budget). Beginning at the bottom of page 50 of the management ordinance, there are a dozen ordinance sections that merely describe potential policies for collecting debt and other potentially revenue-generating efficiencies, rather than specific Municipal Code amendments.

For example, this budget team needed $89,600,000 in debt sales to balance their budget, based on all other assumptions, and so in Section 16 (pages 50 – 51) of the management ordinance, they direct the Comptroller to sell that amount of debt in a sale. On December 23, 2025, Mayor Johnson issued an executive order that places guardrails on how debt can be collected, and exempted medical-issued debt from any sales (such as ambulance debt).

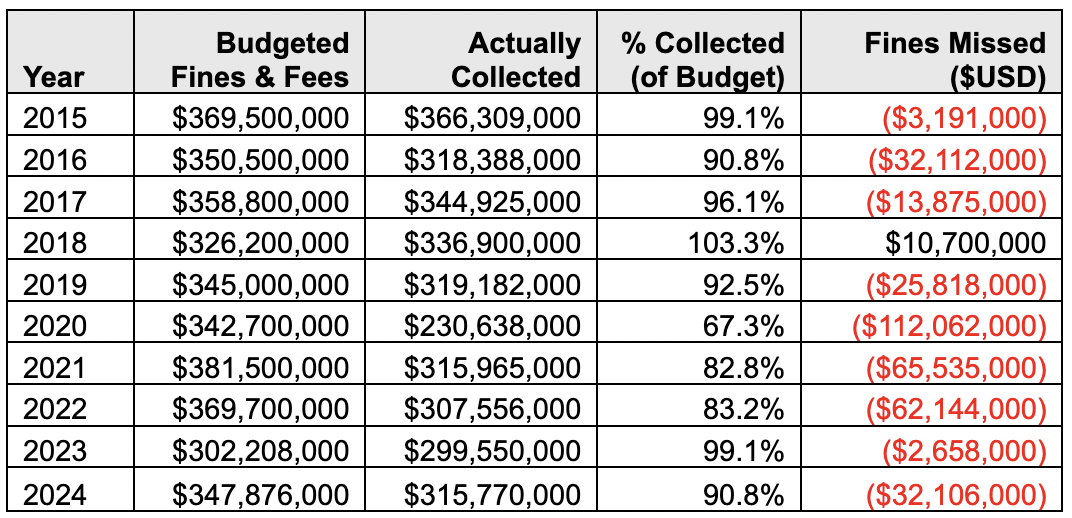

It should be noted that the alleged amount of $1 billion in available debt to collect under the current administration (as reported by Chicago Sun – Times) does not match audited reports of fines, fees, and forfeitures as compared to the budget. Debt collection has fallen since the shutdown era of the COVID-19 pandemic, but shortfalls over the last two administrations total just over $300 million against the budget (see the table published above).

Over the last six years (2019 – 2024), the City’s comprehensive financial audits suggest that the City has collected $1,788,661,000 in fines, fees, and forfeitures against $2,0988,984,000 (an 86% success rate). If the amounts of debt ($1,000,000,000 since 2023) as reported in the news were converted to budgetary figures, it would seem that the City is only budgeting roughly half the debt that could be collected.

However, if the City’s actual performance of collecting debt regularly performs well against its budgeted expectations, it is worth questioning how much debt is viewed as an “off-budget” matter and (correctly) assumed to be not collectible from issuance. It should be noted that if City Council were to improperly assume the percentage of debt that can be collected, this would exacerbate a budget gap.$46,600,000 – Efficiency Improvements: The proposed budget also includes various revenue efficiencies, as suggested by the Ernst & Young consultancy report procured throughout 2025 by the City. These revenue efficiencies, however, were not specifically selected by the budget drafting team, and so Sections 18 through 26 (roughly) of the management ordinance (pages 51 – 53) direct the City departments to enact policies or write Municipal Code amendments.

This raises questions about whether the future Municipal Code amendments will reach the revenue estimates required by this budget. The better approach to amending the budget is to provide the specific Municipal Code amendments that match the necessary and specific policy requirements for implementing the budget. The alternative budget recommendations ordinance does not identify the specific requirements of implementing these budget efficiencies, and instead simply located $46.6 million in “Corporate Fund Savings.”$29,300,000 – Public Right of Way Advertising: The proposed budget also includes a program to advertise on various bridge houses, light poles, and City fleet vehicles. Like the efficiencies section above, this portion of the budget has no Municipal Code amendment associated with it, and solely directs the City to develop a policy for such public right of way advertising (Section 20, pages 51 – 52).

$6,800,000 – Video Gambling: The City Council budget has further issues related to gambling, as it is legally unclear whether the City has the authority to implement the video gambling tax as amended in the revenue ordinance (Article VIII, pages 28 – 30). The video gambling ordinance also raises legal issued with regard to the Bally’s Casino Chicago agreement, and it also will nullify the $4,000,000 annual fee paid by the Casino to the City.

$6,000,000 – Augmented Reality: The City Council budget also is balanced by using an augmented reality sales program, which would allow games like Pokemon Go to be embedded within the public right of way. Like the other efficiencies and revenue sources above, there is no revenue ordinance section associated with this Code, but instead a management ordinance direction (Section 19, page 51).

Modest Property Tax Levy Increase to Save the Chicago Public Library

Mayor Johnson’s original budget proposal included $5 million in library materials cuts (ex., purchasing books) as well as cuts to numerous Library staff and security staff at the Library. Since the Library is included with its own portion of the property tax levy, Alderman La Spata led a group of alders who restored full library services, materials, and security services with a modest property tax increase. The increase will cost roughly $11 for the typical 1st Ward property owner in 2026 to maintain full library services.

What are legally required costs that contribute to the Corporate Fund budget gap?

There are numerous legally required costs that contribute to the Corporate Fund budget gap. These costs, in 2026, include (but are not limited to):

A full advanced, supplemental pension payment to avoid bond rating downgrade (at least $110,000,000)

Backpay to the Chicago Fire Department due to their new contract (at least $166,000,000)

Police settlements: Settlements total more than $80 million on the Corporate Fund, and the City will issue bonds to cover $283 million in global settlement agreements

Contractually obligated pay increases: This includes union staff across departments, from police and fire to other employees on municipal, trades, and services unions.

Pensions: The City is legally required to make actuarially determined payments to its pensions. These expenses cannot be cut (this year’s pension subsidy from the Corporate Fund actually did not increase enough to substantively contribute to the budget gap).

What are other proposals that could be used to balance the budget?

Up to $175,000,000 Municipal Pension Resolution (State of Illinois intervention needed)

The Chicago Public Schools administrative personnel have their pensions managed with the Municipal Employees Benefit fund, which is traditionally (and legally) paid by the City of Chicago. However, from 2020 onward, the Chicago Public Schools have entered into intergovernmental agreements with the City of Chicago, to provide pension reimbursement payments to the City as the MBEAF pension climbs its “pension ramp” (to meet legally-required actuarially defined pension payments).

Beginning with the 2024 pension payment, Chicago Public Schools failed to make their legally required payments, essentially blowing a hole in the City’s budget.

Disentangling the City and Schools pension portions of the MBEAF is a complicated legal issue that would require State intervention.

This issue is further complicated as an elected School Board takes over, meaning that the Mayor of the City no longer retains the traditional seat of power to adjudicate policy disputes such as this one between the City and Schools.

Resolving this matter could at minimum yield the City $175,000,000 in MBEAF pension reimbursement.

Controversy: Pension reform item involving the Chicago Public Schools, outside City Council control

Up to $260,000,000 Garbage Fee.

The Garbage Fee is another controversial tax discussed throughout the 2026 Budget process. The problem with the Garbage Fee began upon its inception, as the fee was only designed to be a partial subsidy of garbage; studying the 2016 ordinance, when the fee was first introduced, the fee only covered roughly 47% of solid waste services (and likely much less than that, if you include the cost of maintaining and developing a sanitation services fleet, ex., garbage trucks).

The garbage fee cannot be fully collected for each address that receives services, because certain dwelling units are not liable for the full fee (for example, eligible seniors receive a 50% discount).

The garbage fee has not been inflation adjusted; an inflation-adjusted garbage fee would need to raise at least $82,000,000.

Garbage service costs have outstripped inflation, and so if the City covered the same percentage of sanitation services as when the fee was implemented in 2016, the fee would need to collect at least $120,000,000, and maybe more than that depending on how you calculate maintenance costs for the garbage fleet.

If garbage service was operated like other functions in the City, such as water or airports, and the garbage fee fully covered the services offered by the City, the monthly fee would likely cost more than $50 per month. The City’s financial future task force studied this matter at length, with a variety of scenarios.

There are numerous arguments for and against raising the garbage fee, but so long as the garbage fee is not inflation adjusted, refuse and recycling services will need to be subsidized by other fines, fees, and taxes in the budget. In the 2026 budget, this means that the Corporate Fund is subsidizing up to $260,000,000 in garbage service with other fines, fees, and taxes.

Ald. La Spata pitched $15/month fee, to get the fund in line with inflation, worth at least $30,000,000 to the budget.

More than $170,000,000 in Corporate Fund Vacancies

In the 2026 Budget, the Corporate Fund includes more than $170,000,000 in vacancies. Focusing specifically on full-time positions, these vacancies comprise more than 14% of the City budget gap. In order to achieve Ernst & Young recommended efficiencies, which include rightsizing the number of employees reporting to supervisors, the City is implementing a substantial hiring freeze in 2026, so the amount of potential savings to be found from cutting vacancies is reduced.

Removing “salvage” (which is the turnover term used to discuss the hiring freeze in the budget), the following vacancy figures were published to the Committee on Budget and Government Operations on December 17, 2025:

$99,633,581 in Corporate Fund vacancies in 2026 not subject to the hiring freeze.

$52,363,949 of those vacancies are under the Police Department.

$14,033,481 of those vacancies are under the Fire Department.

Excluding public safety departments (OEMC, Police, and Fire), there are only $32,957,425 vacancies in the Corporate Fund.

The 1st Ward Office studied vacancies published in each of the last three budgets (2024 – 2026), and found more than $75,000,000 in “persistent” vacancies (ex., positions that had vacancies in each of the last three budgets).

Potential controversy: Police and fire vacancies; Ernst & Young management efficiencies in progress

$147,000,000 in Corporate Fund Overtime Increases

In the 2026 Budget, the City is implementing a transparency-in-budgeting procedure, by rightsizing departmental overtime in the Corporate Fund. This alone comprises at least 12% of the Corporate Fund budget gap in 2026.

Police overtime comprises the largest increase year over year, at $100,000,000.

Fire overtime comprises the next largest increase year over year, at $41,400,000.

The City Council budget group removed a provision from the 2026 Budget, which would require the Chicago Police Department to return to City Council for approvals of overtime beyond the appropriated amount in the original budget document. By analyzing City hiring practices (as you will see below, the Police Department also has the largest segment of vacancies as well), improving hiring practices could help to rightsize overtime. There is a long debate to be had about rightsizing vacancies and overtime in the Corporate Fund, overall.

Potential controversy: Police and fire overtime included

$100,000,000 Corporate Head Tax (“Community Safety Surcharge”)

The original budget proposed by the mayoral administration included a new separate fund, the Community Safety fund, to be funded by a Community Safety Surcharge, more commonly known by residents at the Corporate Head Tax. This was by far the most discussed aspect of the 2026 budget, with 1st Ward residents mixed on the importance of this tax (1st Ward residents in two budget surveys listed community safety functions as a top policy priority, and residents in phone call, email, walk-in, and ward night feedback were mixed on whether the City should implement a head tax). Recent research published by WBEZ finds a lack of clear evidence of the impact of the head tax on jobs and economic performance in Chicago, but the ideological messaging is by far more charged among residents (for or against) rather than concrete discussions of evidence or the amount of the tax.

The most recent head tax proposal would charge $396 annually ($33/month) per employee at corporations with 500 or more employees. For an employee earning $39,600 annually, this would effectively be a 1.0% tax for the employer; for an employee earning $100,000 annually, the effective tax rate falls below 0.4%.

Controversy demonstrated in the public sphere during this budget cycle, ideology versus fact

More than $90,000,000 in inflation-adjusting and revising electrical fees.

The budget gap is exacerbated by numerous aspects of State Law, which pre-empt the City’s ability to revise various taxes. As residents are being more aware of the impact data centers, quantum computing development, and Artificial Intelligence are having on our water and electrical supply (and electrical bills), it must be underscored that the City’s electrical taxes are limited such that they have not bee inflation adjusted in 30 years. For example, in the 1997 budget, electrical taxes were $90,600,000 for the City; in 2026, the City expects to collect $96,582,895 in electrical taxes. This exhibits a virtual budget gap; as the City cannot inflation adjust electrical taxes, it needs to find $90,000,000 in additional revenue sources to maintain the same level of services these funds covered in 1997.

Potential controversy: Appearing anti-business in the new technology-oriented State economy

$80,000,000 Lost due to Grocery Tax Pre-emption.

The State of Illinois previously collected a grocery tax, distributing the amounts to municipalities as owed. The State of Illinois stopped this practice, basically ending the statewide practice but allowing municipalities to opt-in to continue collecting the tax. Given the timing of this practice with grocery cost inflation, and the misperception by some that this would be a new tax, the City lost $80,000,000 when the State of Illinois passed this law and public perception sharply turned against it.

Controversy: Grocery inflation issues

Unclear revenue amount: Creating a citywide Smart Streets Pilot.

The City has been working on a Smart Street pilot, to equip CTA buses and city vehicles with cameras to enforce traffic and parking violations that impede bike and bus lanes. A good governance reform could expand this proposal to match the Transportation Network Provider (ride share) congestion area map; expand to specifically congested corridors; or citywide implementation.

Up to $73,200,000 in restoring a rate-based Ride Share Tax.

In order to win votes, both the mayoral and City Council budget proposals revised their Ground Transportation tax proposals. These are specifically taxes paid on Transportation Network Provider trips (TNP), more commonly known as ride share fees. The City Council budget exacerbates the budget gap by eliminating a rate-based tax, which would essentially mean that if you take shorter ride share trips, you are charged accordingly.

Additionally, ride share fees have not been inflation adjusted. The City can easily raise $29,000,000 to $33,000,000 simply by inflation adjusting TNP taxes.

$67,000,000 in General Obligation Bond Savings.

The 1st Ward Office has identified published bond schedules for the City’s 2026 General Obligation bonds, which differ from the amounts originally published in the 2026 Budget Recommendations due to the completion of the 2025 issuances. The Chief Financial Officer’s staff have confirmed the published debt schedules in the City’s bond documents are correct, and the 1st Ward Office is further discussing these potential savings with City Budget officials.

Up to $68,000,000 Inflation-adjusting Property Taxes

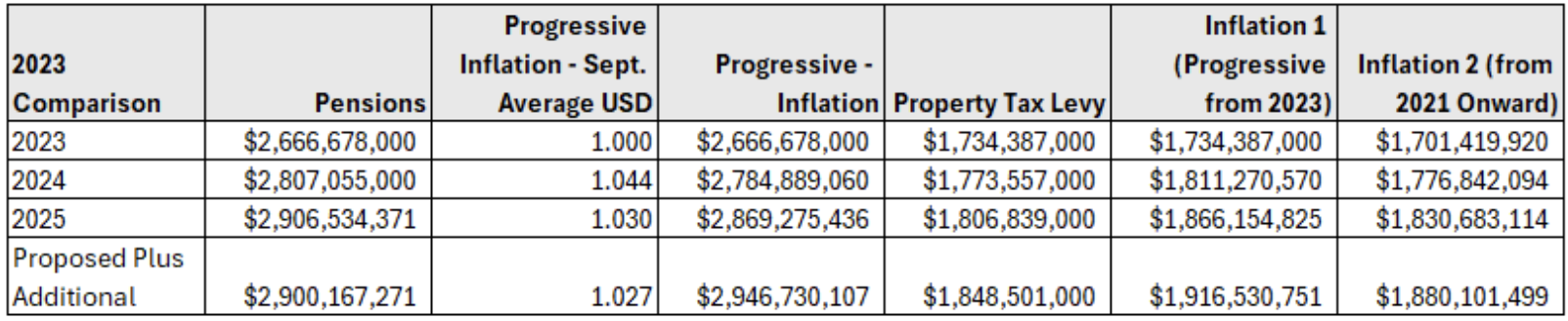

From 2021 onward, the City of Chicago is by-law permitted to raise a portion of the property tax levy to cover pension payments. This is a highly controversial area of policy, especially as Cook County endures a number of controversies related to property taxes, including the relationship between the Board of Review and Cook County Assessor with regard to the value of commercial property assessments.

Given the additional impact gentrification and development is having on property values across the City, as well as the inability of large megadevelopments to come to fruition (if even 10% of Lincoln Yards and The 78 had been completed prior to 2025, for example, that would have produced at least $6,000,000 in additional property taxes in the 2026 budget), and the impact of recent reassessments and Board of Review decisions on property tax bills, raising property taxes is as much of a lightning rod as anyone could find in the City.

That said, it must be noted that the City itself has not been raising the property tax levy with inflation at least since the 2024 budget, and in 2026 that means the property tax levy could have been raised between $31,000,000 and $68,000,000 (thus comprising up to 4% of the budget gap).

For further reference on the issue related to property taxes, please compare the recent budgets (2023 – 2026) progression of property tax levies and pension payments:

In the table above, you can see that one major issue is that as the City has been climbing its “ramp” to make actuarially defined pension payments plus supplemental payments, the property tax levy has not kept pace with inflation while the pension payments have tracked (or exceeded) inflation. This creates additional budgetary strain, even if property taxes are well-known as such a controversial issue that a substantive increase could not occur.

Up to $20,000,000 Inflation-adjusting so-called “Sin Taxes.”

There are a number of Municipal Code items that simply need to be inflation adjusted. Inflation adjusting taxes associated with alcohol, nicotine, and related substances, could raise substantial revenue. These types of proposals are usually quite controversial, due to being viewed as anti-business.

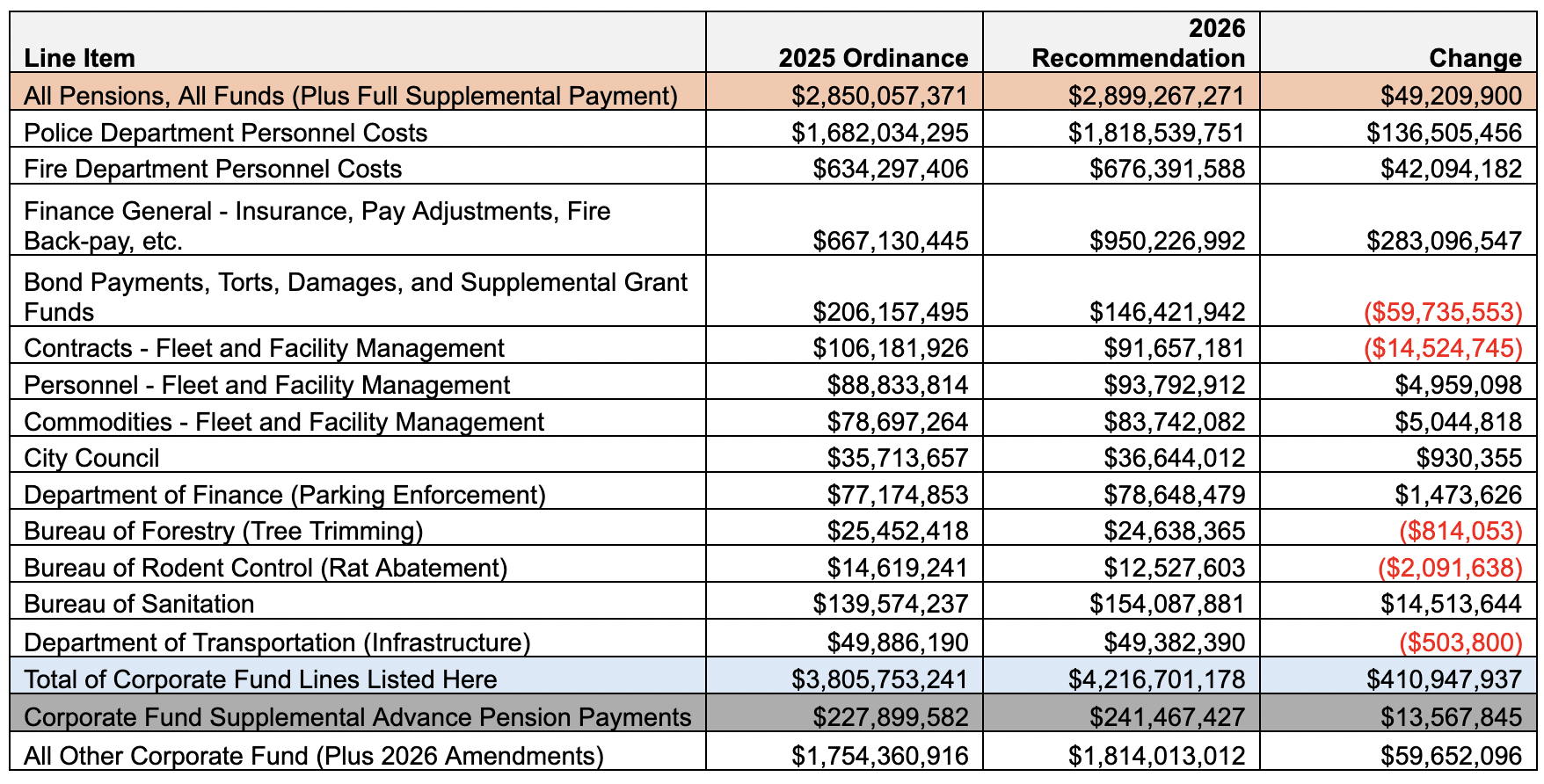

Considering Cuts

Many 1st Ward residents regularly ask why we don’t often discuss cuts. There are three major reasons:

As a matter of constituent services, the majority of residents ask about improving or expanding services, rather than cutting services. As a general rule, 1st Ward residents want to see more and better services.

As a philosophical matter, Alderman La Spata believes that we can find more efficient routes to improve services that do not involve cuts. We work hard to advocate for our residents at City Hall with that mantra.

Finally, since the budget gap lives in the Corporate Fund, the major issue is that the vast majority of expenses in the $6.1 billion fund are for public safety personnel expenses, overtime, and backpay (more than 43%); legally required expenses such as pensions (more than 13%); and, personnel expenses such as health insurance and wage adjustments (more than 12%). If one assumes that residents do not wish to see public safety functions cut, the next largest line items reside in departments and services functions that are already seeing cuts or moderate (at best) increases (such as Forestry, Rodent Control, and Infrastructure).